The route to the southern edges of Picardy from south-east London is a straightforward one these days; the town of Albert can be reached in around four hours via the Channel Tunnel from Lee or Hither Green. A variant of the journey was taken by numerous young men just over a century ago

This week sees the centenary of the beginning of the Battle of the Somme on 1 July 1916 and many of those that made that short journey never returned, killed in the initial onslaughts and buried in a foreign field. The story of the first day has been told numerous times before both factually (such as here) and fictionally, although few more eloquently or poignantly than by Sebastian Faulks who described a scene a day or two before the offensive began:

As they rounded the corner, he saw two dozen men, naked to the waist, digging a hole thirty yards square at the side of the path. For a moment he was baffled. It seemed to have no agricultural purpose; there was no more planting or ploughing to be done. Then he realized what it was. They were digging a mass grave. He thought of shouting an order to about turn or at least to avert their eyes, but they were almost on it, and some of them had already seen their burial place. The songs died on their lips and the air was reclaimed by the birds.

Sebastian Faulks (1994) Birdsong (London, Vintage), p215

The sheer enormity of the scale of human loss becomes obvious when looking at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website – there are almost 18,000 names of deaths on first day of the battle.

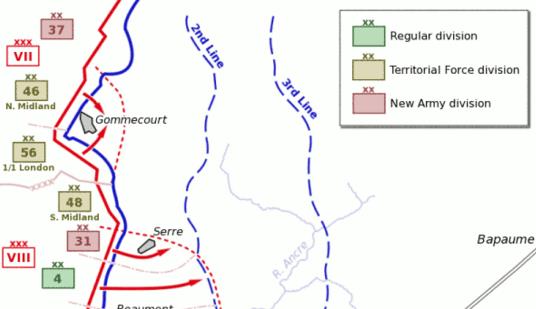

This post focuses on the role of a local regiment – the 56th Division, 1st/5th Battalion of the London Regiment (London Rifle Brigade), they were a ‘City’ Regiment but many of their soldiers were from south east London. Their role that day was essentially a diversionary one to try to divert German troops away from a more significant push further south on the Somme, the secondary aim was to help secure the northern flank around Gommecourt thus pushing the German’s back to positions that would be less easy to defend.

Map Source Wikimedia Commons

Initially the London Regiment met with success and took the first and second German lines, but there was much more resistance from the third line and the British suffered considerable causalities and were driven back to their original lines. Of the 826 from the regiment at the start of the day 275 were listed as dead by the end of the day on the CWG site. Just 89 came through the day alive and unwounded.

There were are least a dozen local men who died that day at Gommecourt with the London Rifles. It is worth reflecting on some of those young south London lives cut short on the first catastrophic day of battle where the worth of the human life seemed to count for so little. They will have climbed out of their trenches at around 7:30, none seen again alive and with most their remains were never identified.

James Frederick Wingfield – 36 Burnt Ash Road

James was a 30 year old Rifleman of the 1st/5th Battalion of the London Regiment (London Rifle Brigade) He was the oldest of 8 children (in the 1911 census) of son of James Peter and Elizabeth, the former was Company Secretary for a wine merchant. The family originated in East London, where James had been born in South Hackney and by 1911 were living at 9 Effingham Road; in Civvy street, James was an Accounts Clerk.

In the intervening five years Frederick had married Ada Gertrude Glanville and had moved just around the corner to 32 Burnt Ash Road – her parent’s home – probably close to the postcard depiction below of around that time (source e bay February 2015).

There is no known grave for James Wingfield and he is remembered along with 72,194 others at The Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme to missing British and South African men, who died in the Battles of the Somme of the First World War between 1915 and 1918. It is just a couple of miles down the road from Gommecourt. James and another local man who died the same day, 20 year old Arthur Webber from 69 Eltham Road, are also commemorated on the War Memorial at the former St Peter’s Church site.

© Copyright Stephen Craven and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

Cecil Ravenscroft – 94 Mount Pleasant Road

Cecil was a 19 year-old rifleman born in Chicester in East Sussex in 1896, to Byfleet Charles Ravenscroft who hailed from Worcestershire and Catherine from Swansea. They seem to have been a family that moved around a lot this oldest brother was born in Lewisham in 1890, but in the following year’s census they were in Ifield in West Susseex (now part of Crawley). In the 1901 census they were back in Lewisham, although only visiting someone in Brockley Park. Cecil’s younger brother, Charles was born in Lewisham in 1895.

Cecil’s father died in 1911, before the census was conducted on 2 April. The family was living at 49 Albacore Crescent and the 14 year old Cecil was working as a clerk, perhaps in the ‘City.’

By the time of Cecil’s death, the remaining members of the family were living at 94 Mount Pleasant Road. He was buried at Hébuterne Military Cemetery, about a kilometre south of Gommecourt.

Picture from CWGC Website which allows reproduction of images and material elsewhere

Frank Dension Chandler – 23 Vanbrugh Park

Corporal Frank Chandler was born in Camberwell in 1893, his parents were Gibbs William and Lizzie Chandler who were from Camberwell and Isle of Dogs respectively – they were living at Liford Road, Camberwell in the 1891 census. In 1901 the family was still at Lilford Road, Frank was the fourth oldest of the six children of the family, but his mother Lizzie had died in 1898.

By 1911 they had moved to East Dulwich Grove, his father having married Alice from Hamstead in Kent in 1907; by 1916 the family was living at 23 Vanbrugh Park. In Civvy Street Frank (pictured – source here) worked for Lloyds broker’s Nelson Donkin & Company

By 1911 they had moved to East Dulwich Grove, his father having married Alice from Hamstead in Kent in 1907; by 1916 the family was living at 23 Vanbrugh Park. In Civvy Street Frank (pictured – source here) worked for Lloyds broker’s Nelson Donkin & Company

Like James Wingfield, there is no grave for Frank and he is remembered at Thriepval.

Richard Hopf – 9 Davenport Road

Rifleman Richard Hopf had been born in Catford in 1888, his parents Emilie and Paul were from Germany. Paul seems to have died sometime between the 1886 and the 1891 census. The family was not recorded in the 1901 census but in 1911 Richard was living was his mother and four siblings in Westdown Road in Catford – he is listed as a Counting House Clerk.

In the early stages of the war there were a lot of attacks on German nationals, something that the blog covered in relation to Deptford a couple of years ago, many were deported. With an English born family, who presumably would have had to stay behind, Emilie remained in Catford. Several of the family subsequently Anglicised their name to ‘Hope’, including Richard’s older brother, Paul.

Richard Hopf is listed as dead on the CWGC website and was ‘buried’ at the now peaceful looking Gommecourt 2 Cemetery.

–

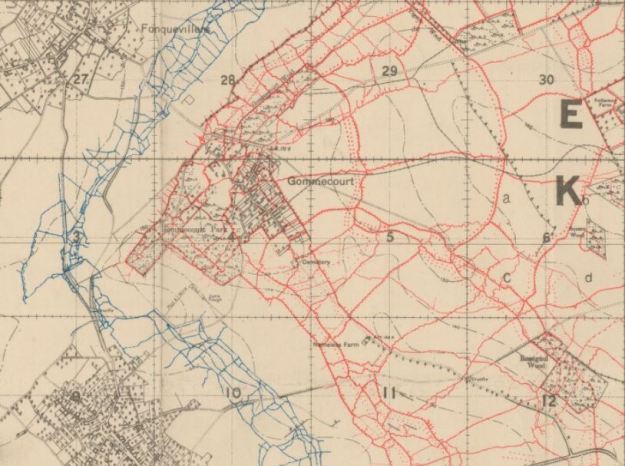

Returning to the Somme, the initial push on that first terrible day foreshadowed what was to come – there was to be little success at Gommecourt – the OS Trench maps from around the end of the ‘battle’ six months later, show almost no progress from the initial lines. Gommecourt was still under German control.

I will leave the final words about that the catastrophic losses from those initial assaults to someone who has written extensively about the Somme and particularly about Gommecourt, Alan McDonald

The men of the 56th and 46th Divisions had been sacrificed to no end. It was predictable, it was unnecessary, it was criminal.

Excellent blog for the 100th anniversary of the first day of the Battle of the Somme. I also really like the book Birdsong and Faulks’ description of the night before the attack is an incredible piece of writing. It is written from the view of the soldiers which not many books do.

Thank you; I loved ‘Birdsong’ and it seemed so apt to quote that passage. In terms of the WW1 experience of the ordinary soldier I prefer Sebastian Barry’s ‘A Long, Long Way’ and possibly ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ which is from the German perspective, by Erich Maria Remarque.

I have read both of them and they are really good. I haven’t read All Quiet on the Western Front since school. I will have to reread it.

Pingback: It Isn’t Far from Lee to Gommecourt …. | Running Past | First Night History

Very sobering. I too need to read All Quiet on the Western Front

It is very sobering indeed. Stood on torrential rain for a couple of minutes this morning thinking and reflecting..

To me this was the one essential thing I read about the Somme all weekend. A beautiful account which brings this gigantic disaster into a sharp, personal set of details and will resonate with me as I walk around those streets. Yes, in spite of those who want to divide us, we are all connected, past, present and future… Thank you

Thank you for your kind comments, that was the idea behind it. I wanted to remember it in some way, if for no other reason that there had been such a callous disregard for the lives of the young men in khaki uniforms. The full scale of the Somme military catastrophe makes it difficult to comprehend, but telling the story through a few lives cut short, whose streets I run, walk and drive along seemed to make sense to me. The streets have changed, numbering may be a bit different and one of the houses has certainly gone, but for me, at least, but I remember and reflect on them as I pass.

Pingback: Philip Kingsford – A Pioneering Lewisham Triple Jumper | Running Past

Pingback: Remembering Lewisham’s World War One Combatants | Running Past

Hello Paul. I have only just come across this particular blog post. Thank you again.

By coincidence my great uncle Ernest Holmes was a 22 year old sergeant in the 56th London – in the 1/13 Kensingtons (based in SW London, he came from Fulham). He was wounded in the first hour of the first day of the assault on Gommecourt on 1 July 1916, and died 5 weeks later as a result of his injuries. Last month I visited the village of Hebuterne, the first member of Ernest’s family to do so, and walked the surrounding fields which are largely unchanged from the WW1 maps. A totally depressing experience in the knowledge that of the thousands of teenagers and young men in their early twenties, many from South London, who were lined up in the mud in those couple of fields that Saturday morning, the casualty rate was almost 60%. In an assault that was never intended to achieve anything other than drawing enemy fire. Criminal indeed.

It was one of the most depressing posts that I have researched/written, so many stories like your great uncle’s, so many utterly pointless deaths.