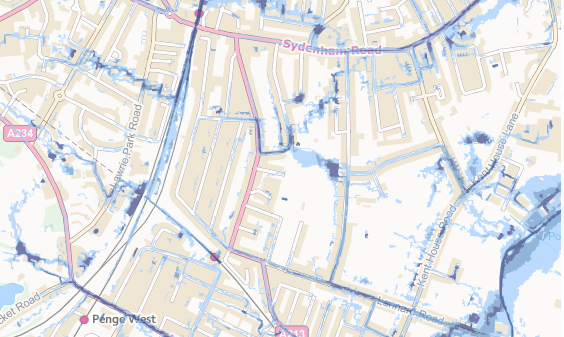

There is evidence of at least a dozen streams having flowed from the high ground of Sydenham Hill to the River Pool. Many no longer flow – some victims of changing water tables and spring lines, others lost to Victorian drainage. Running Past has already covered a couple of these – Adams’ Rill and Wells Park Stream, and over the next few months will cover most of the others. This post covers a stream to the south of the other two which, as far as I can see, is currently nameless, but will be referred to as Pissarro’s Stream, for reasons that will become obvious as we proceed downhill.

The stream seems to have emerged around the location of what was originally called Horner Grange (above), just east of Charleville Circus. The upward pointing contour lines (streams erode, so notches appear on contours) peter out around the Grange. Horner Grange was built as home to William Knight who made a fortune diamond mining in South Africa in 1884, and he lived there until his death in 1900 – he was buried at West Norwood Cemetery. After Knight’s death, the house became a hotel and then the freehold was bought by Sydenham High School in 1934. The Grange remains but its grounds have been heavily built upon by the School and there are no publically visible hints of fluvial activity.

A contour line notch below the school suggests a route across a small cul-de-sac, The Martins, off Laurie Park Gardens. There is a small depression in the road which is clearly visible.

Just below it, on the stream’s course was the large Westwood House, once home to Henry Littleton – who had made his fortune from Novello’s, the music publisher. Littleton invited many of the leading lights of classical music of the era to stay and the music room saw performances by both Dvorak and Liszt.

The house had started more modestly around 1720, but there were several ‘water features’ including a small lake, perhaps fed by the Stream – this is visible on the Ordnance Survey map below (on a Creative Commons via the National Library of Scotland) from the 1860s. The scale had reduced by the time the map was redrawn in 1897 . Westwood House later became the Passmore Edwards Teacher’s Orphanage and was demolished in 1952 to make way for the Lewisham’s Sheenwood council estate.

Just below Sheenwood, the stream comes to one of the more famous artistic views in South London – Pissarro’s painting of The Avenue, Sydenham dating from 1871 (Via Wikipedia on a Creative Commons). Pissarro was to later note to his son ‘I recall perfectly those multicoloured houses, and the desire that I had at the time to interrupt my journey and make some interesting studies.’ (1)

Pissarro was one of a number of artists who fled France at the beginning of the Franco Prussian War in 1870. While unlike some of his fellow artists, Pissarro wasn’t at risk of conscription – he carried a Danish passport but left to escape the Prussians in his village of Louveciennes. He settled in Norwood, close to his mother who had already fled France with other members of her family.

The stream would have flowed around where Pissarro set up his easel on what was then Sydenham Avenue, now Lawrie Park Avenue, although the stream was almost certainly not visible on the ground at that point in time – it wasn’t marked on the map surveyed in 1863 (see above).

It is often said how little the view has changed, certainly the backdrop of St Bartholomew is still there and the road remains. While the view would have been similar until the 1960s, Dunedin House to the left is still there, but less visible. The street is now dominated by 1960s or 1970s housing, the mode of transport is much changed and the trees are much bigger even at a similar time of year to the original (see below).

It is often said how little the view has changed, certainly the backdrop of St Bartholomew is still there and the road remains. While the view would have been similar until the 1960s, Dunedin House to the left is still there, but less visible. The street is now dominated by 1960s or 1970s housing, the mode of transport is much changed and the trees are much bigger even at a similar time of year to the original (see below).

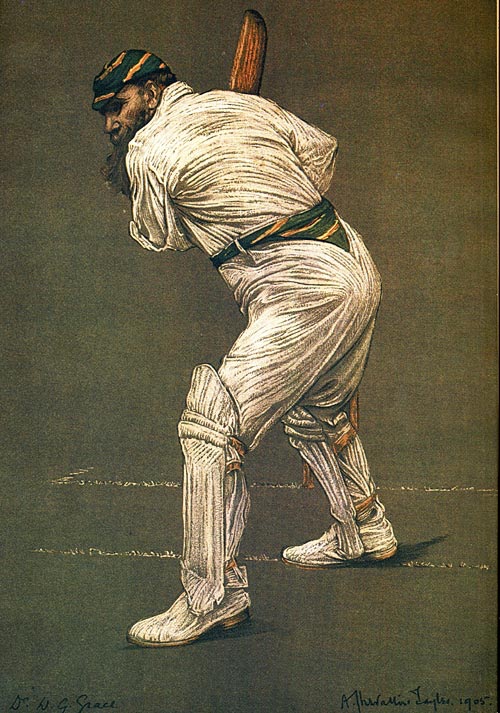

Beyond Pissarro’s view, the stream would have crossed Hall Drive, where there is a perceptible dip, and then dropping a little further to Lawrie Park Road – the hollow is more distinct there. The Stream would have flowed close to the site of the home of one of Sydenham’s more famous former residents, the cricketer WG Grace – whose time in South London was celebrated in Running Past around the centenary of his death.

The short-lived Croydon Canal (opened in 1809) and then its successor the London and Croydon Railway will have blocked the passage of the stream. Whether the stream was flowing when the former was built at this point is debatable, and if it was, it is unclear as to whether it was culverted underneath or allowed to drain into the Canal.

Over the railway, Venner Road is crossed by the stream at Tredown Road, the course is clearer from contours than it is on the ground. Beyond another faint dip on Newlands Park, the ground flattens out into lower Sydenham. The route, becomes much less clear to follow. Even the Environment Agency Flood Risk maps which show 100 year surface flow peaks and often indirectly indicate former streams don’t help much here.

However, they show clearly the two possible routes for the stream, either side of a small hill that is obvious from Kent House Road to Kangley Bridge Road. There are possible routes either side of the knoll.

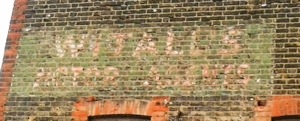

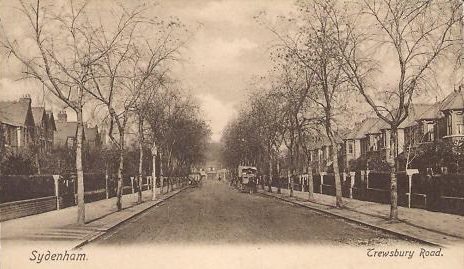

The northern option around the less than grassy knoll would necessitate crossing Trewsbury Road (picture above – source eBay November 2016) and then passing close to the Kilmore Grove former ghost sign and the home of the author Graham Swift’s father in Fairlawn Park before a confluence with Wells Park Stream around Home Park.

The southerly option would have seen a flow through Alexandra Recreation Ground where there is a very slight dip, through another on the elegant Cator Road Beyond Woodbastwick Road the boundary would have bifurcated from the Indeed, the Environment Agency surface water flood maps, which show 100 year extremes, and often highlight to course of former or hidden streams suggest potential flows either side of the hillock.

There are a couple of southerly options – Bing maps has a bit of blue indicating a stream through some allotments off Kent House Road – it wasn’t visible either on aerial photographs or marked on Ordnance Survey maps and despite the warm sun of the late afternoon when I was doing the ‘fieldwork’ no one was visibly tending their vegetables. Notched contours on Ordnance Survey maps would support this route though, as do some ‘puddle’s on Environment agency map above. However, as the flows onwards from here would have seen the pre-development contours obliterated by the Beckenham and Penge Brick Works, so any certainty is hard to come by.

The second option would take the stream close to the junction with Kent House Lane and Kent House Road, alongside some other allotments, there is flowing water for around 50 metres to a confluence with the Pool, including a small bridge that carries National Cycle Route 21. As there is water flowing and any post on a stream is better with an actual fluvial flow this would be my preferred option for the final metres of Pissarro’s Stream.

Notes

- Quoted in notes adjacent to painting in Tate Britain’s ‘Impressionists in London, French Artists in Exile (1870-1904)’