There were serious floods in Lewisham in September 1968 which Running Past covered on their 50th anniversary. Previous floodings of the Ravensbourne, Quaggy and Pool were mentioned in passing at that stage, including a reference to some very serious ones 90 years earlier in 1878. It is to these that we now turn our attention. In syndicated press reports it was reported that in Lewisham the ‘whole of the village (was) 3 or 4 feet deep in water’ (1).

The 19th century had seen several inundations of Lee and Lewisham – Victorian historian FH Hart noted very serious floods in 1814 as the ice melted following one of the last big freezes of the Little Ice Age – the last time there was a frost fair on the Thames. There had also been really bad ones in 1853 and another flooding following a period of heavy rain on Christmas Eve 1876 – but the 1878 ones were described as being ‘the worst in living memory’ (2).

The spring of 1878 seems to have been a very dry warm one with surfaces left hardened. From the early hours of Thursday 11 April 1868, 3¼ inches (83 mm) of rain fell in 12 hours while this was the highest for 64 years, it was substantially less that the rainfall that led to the 1968 floods.

Unlike the floods 90 years later in 1968, where the devastation was similar in the three catchments of the Ravensbourne, Pool and Quaggy; in 1878 it was mainly in the Quaggy and the Ravensbourne below the confluence with the Quaggy near Plough Bridge – named after the pub of the same name (pictured just before its demolition around 2007).

This is not to say the other parts of the catchment escaped – there was flooding higher up the Ravensbourne with Shortlands impassable; the local landowners at Southend, the Forster’s, home was flooded and the nearby bridge on Beckenham Lane (now Hill Road) was washed away – the bridge that replaced is pictured in the background of the postcard below. The cricket pitches by Catford stations were flooded up to sills of pavilion windows. Similarly, Bell Green was impassable on the River Pool (5).

The local press though focussed on the Quaggy and lower Ravensbourne – we’ll follow the trail of destruction and damage downstream from Lee Green.

At Lee Green the basement of the shops at what was then called Eastbourne Terrace on Eltham Road (to the left of the photo, a couple of decades later) were completely flooded out with seemingly some flooding at ground level too.

Further downstream where the Quaggy is bridged by Manor Lane, the road was impassable. The area was in a period of transition from its rural past to suburbia, having been opened up by the railways through (but not stopping at) Hither Green, Lee and Blackheath. There were still some larger houses from the exclusive village past – all situated in the higher ground around Old Road and on the hill between Lee High Road and Belmont Hill. The lower lying fields were under water as was any housing built on the flood plain. The same continued downstream through what is now Manor Park – the course of the Quaggy was a little different at that stage though.

The houses that had been completed on what is now Leahurst Road (then a dog leg of Ennersdale Road) which backed onto the Quaggy were badly flooded. As a result of the 1876 floods, the local Board of Works had built a large concrete wall, an early use of the material, to try to reduce the impact of future floods. It was described as ‘perfectly useless’ as water bypassed it and inundated the houses in Eastdown Park. The wall is still there – extended upwards a little after the 1878 floods.

There was a small dairy on Weardale Road, probably next door to the Rose of Lee. Unsurprisingly it became flooded and the cowherd turned out the 30 cows who were found wandering in the water on Manor Park. The were taken to the higher ground of Lee Manor Farm. Elsewhere in Lee, pigs were drowned.

Beyond the Rose of Lee the relatively newly built Eastdown Park bridge ‘blown up by the force of the water.’ The bridge between Weardale Road and Eastdown Park also seems to have been destroyed.

The food waters became deeper as they went down Lee High Road, up to 1.2 metres (4’) deep in the houses of Elm Place, just before Clarendon Rise (then Road). The Sultan on the other side Clarendon Rise was badly flooded too – the third time that this had happened in a decade as the publican, Robert Janes, explained in the press. The pub is pictured below from the next century.

Beyond the Sultan, flood waters flowed both over and under the road – at one point it was expected that the culvert from the bottom of Belmont Hill to St Stephens church might be destroyed but in the end it was just the road surface that was wrecked – this is the high pavement that now stands in front of the police station.

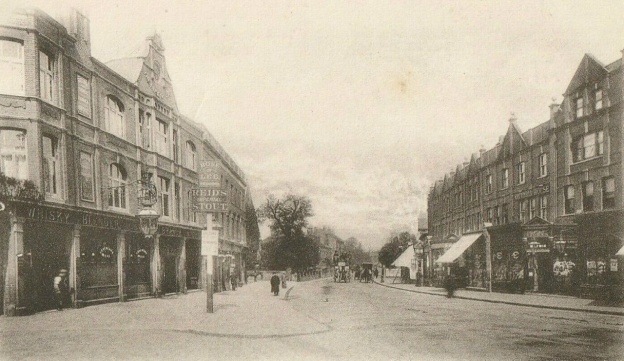

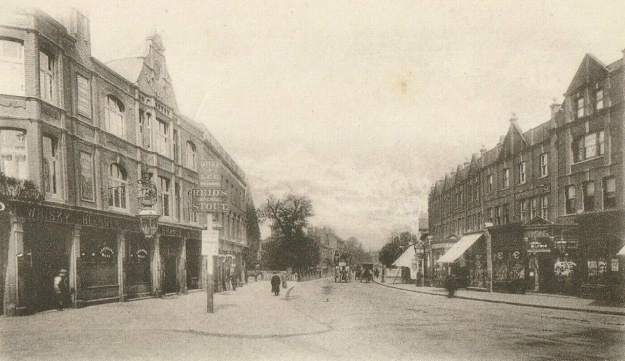

The roadway in front of St Stephens several feet underwater – with the Roebuck, Plough and other pubs such as the Albion all flooded. Boats used to ferry people through Lewisham. There was a real bottle neck around Plough Bridge, the ‘utter insufficiency’ of the narrow Plough Bridge to carry off ordinary storm water was regarded as one of the causes too. The whole area around Lewisham Bridge (pictured below from a few decades later) badly flooded, particularly Molesworth and Rennell Streets and unsurprisingly Esplanade Cottages in the middle of the Ravensbourne, along with the pub the Maid in Mill and rest of Mill Lane.

An iron girder bridge at Stonebridge Villas was washed down along with a wall by the railway, built to try to reduce flooding a year before was washed away – hundreds of houses on the lower lying parts of what became the Orchard estate to the east of the Ravensbourne were inundated. It was the same with the market gardens on the western side, along with large swathes of Deptford. Virtually all the area around the Ravensbourne on the map below from 15 years later was left underwater.

In addition to the high rainfall there was a clear underlying cause which was summed up well by a local man, Frederick Barff, who had grown up in Lee when it was still rural but was living in Eastdown Park in 1871 and if still there in 1878 would have been flooded out. He observed that prior to the development of Lee from the mid-1850s while there had been flooding, it initially stood in large areas of fields which absorbed the runoff without major consequences. The growth of Victorian suburbia had led to increased run off and more water ending up in rivers and stream and at a quicker pace (6).

In the immediate aftermath a temporary wooden bridge over the Quaggy between Weardale Road and Eastdown Park was approved the following day by the Metropolitan Board of Works (7).

There was a public meeting at the Plough on the Friday (next day) to ‘consider the best means of alleviating the distress amongst the poor of Lewisham, Lee, Blackheath and Catford. Crowded by the clergymen, parish officials and leading tradesmen of the district.’ In days before the state intervened in disasters like this it was left to charity to provide ‘coal and relief to those poor people in the district’ whose homes had been flooded. Over £200 was collected or promised for the Lewisham and Lee Inundation Relief Fund – with £120 going to the parishes of St Mark and St Stephen in central Lewisham that had been worst affected; £50 for Ladywell; with £50 for Lee and Blackheath.

So, what happened afterwards? The approach that was used was one that continued towards the end of the 20th century and the 1968 floods – straightening and deepening rivers to try to move water on more rapidly. This happened on the Quaggy behind what is now Brightfield Road – as the maps from 1863 and 1893 show. The Quaggy was also moved and straightened between Manor Park and Longhurst Roads – this happened a little later once the land was developed for housing.

Several bridges were replaced – the partially destroyed Eastdown Park bridge was rebuilt and replaced with a girder one (see below from the river), the river level is lower there now too, although whether this happened post 1878 or 1968 isn’t immediately clear (8).

Plough Bridge was replaced in 1881 by the Metropolitan Board of Works (9) having been preceded by ‘general dredging and clearing the channels of the river’ (10). Later a new sewer between Lee Bridge and Deptford Creek was constructed to try to take some pressure off the rivers from run off (11).

Another bridge replaced by the Board of Works was the one on Lee Road. Previously this had been a ford and footbridge, but a large single span bridge replaced it following the floods, presumably with a lowering of the river bed (12).

The underlying problems remained though, making flows quicker may alleviate problems in one location but without storage and a whole catchment solution, including the ability to control flows on the Thames it wasn’t much better than a sticker plaster. The fields that had acted as sponges continued to be developed and increased run off. In reality, not much had changed by the 1968 floods and it took the development of flood storage in Sutcliffe Park (pictured below) in the early 2000s to really make much difference. Without it Lewisham would regularly flood – it is pictured from late 2020.

Notes

Most of the information for this post comes from the Kentish Mercury of 27 April 1878 which covered the flooding and its aftermath in depth. Readers can assume that contemporary information comes from there unless otherwise referenced.

- Dundee Courier 12 April 1878

- Kentish Mercury 20 April 1878

- ibid

- ibid

- ibid

- ibid

- Kentish Independent – 13 April 1878

- Woolwich Gazette 31 July 1880

- Woolwich Gazette 1 October 1881

- Kentish Mercury 16 October 1880

- Woolwich Gazette 17 June 1882

- Woolwich Gazette 31 July 1880

Credits

- Census and related data comes via Find My Past, subscription required

- The Ordnance Survey maps are on a non-commercial licence via the National Library of Scotland

- Postcards of Lewisham Bridge and what was then Beckenham Lane are via eBay from 2016

- The photograph of the Sultan is used with the permission of Robert Crawford, the great grandson of the Craddocks, licensees there in the 1920s, it remains his family’s copyright

- The photograph of the destroyed bridge in Eastdown Park is from the collection of Lewisham Archives and remains their copyright, but is used with their permission

By the end of World War 2 a niche market was found – wireless repairs, known as Lee Radio Services run by Albert, known as Bert Allen, pictured above with his wife Betty and eldest son Derek. Bert died in 1972 but the business continued, run by Betty, and an engineer who eventually bought out the business. Betty continued to live behind the shop until she passed away in 1984. The property was sold at that point and around the same time the name caught up with technology and became Lee TV Services. Most of this century has been spent reverted to a previous trade – an off licence, a combination of Manor Park Wines and Cost Less.

By the end of World War 2 a niche market was found – wireless repairs, known as Lee Radio Services run by Albert, known as Bert Allen, pictured above with his wife Betty and eldest son Derek. Bert died in 1972 but the business continued, run by Betty, and an engineer who eventually bought out the business. Betty continued to live behind the shop until she passed away in 1984. The property was sold at that point and around the same time the name caught up with technology and became Lee TV Services. Most of this century has been spent reverted to a previous trade – an off licence, a combination of Manor Park Wines and Cost Less.

The links have their origins in the late 9th century when

The links have their origins in the late 9th century when