Hither Green has a rich and interesting history; this post was written to ‘accompany’ a walk organised as part of the 2018 Hither Green Festival, it can be used to independently to walk the route (its a circuit of around 1.8 miles) or as virtual tour of the area. The ‘walk’ is divided into sections which relate to the planned stopping points – each of which is full of links to other posts in the blog which will have more detailed information.

Starting Point – Before the Railway

Hither Green station is the perfect place to start the walk as the railway ‘made’ the area. At the time of the railway arrived in Hither Green in the 1860s, it didn’t stop – it was to be a junction until the mid 1890s. When the South Eastern Railway navvies constructed the embankment and cutting through the area, Hither Green was largely rural, surrounded by farms as the map below shows – the farms including several covered by Running Past – North Park, Burnt Ash and Lee Green.

Hither Green Lane was there with several large houses but the main population centres were outside the area – the elongated Lewisham stretching all the way along what is now the High Street and Rushey Green, the three parts of Lee – Lee Green, the area around the church and Old Road, the latter with the Manor House and the farm and servants housing of Lee New Town.

While Hither Green remained a junction until the 1890s, the edges that were closer to other stations started to be developed – for example Courthill Road started to be developed from 1867, Ennersdale Road during the 1870s. Then roads like Brightside, Mallet and Elthruda began to be developed in the late 1870s and early 1880s. Everything changed with the opening of Hither Green Station on 1 June 1895 – the area lost its rural feel, most of the remaining large houses were sold and the Victorian and Edwardian houses and ‘villas’ built.

The Prime Meridian is crossed and marked in the pedestrian tunnel at Hither Green station, most of the walk will be in the western hemisphere..

Springbank Road & Nightingale Grove

A V-1 attack on devastated the area on the western side of the station on 29 July 1944 killing five and destroying a significant number of homes, as the photograph (below) from the now closed ramp up to Platform 1 shows. It was one of 115 V-1 rocket attacks on Lewisham that summer – the most devastating had been the previous day when 51 had died in Lewisham High Street. Soon after the war nine prefab bungalows were put on the site; with the council bungalows probably appearing in the early 1960s. The Beaver Housing Society homes on the corner of Nightingale Grove and Ardmere Road also replaced some of the homes destroyed – there are glazed tiles naming the landlord which is now part of L & Q Group.

© IWM Imperial War Museum on a Non Commercial Licence

Ardmere Road (covered in a 2 part post) was built in the 1870s but was considered one of the poorest in the neighbourhood by Charles Booth’s researcher Ernest Aves in 1899 – he described it as one of the ‘fuller streets, shoddy building, two families the rule.’ It was marked blue – one up from the lowest class.

The area was looked unfinished to Aves and there was even a costermonger living in a tiny tin shack with their donkey on the unfinished Brightside Road in 1899, along with a temporary tin tabernacle. This immediate area was very poor and in ‘chronic want’ compared with the comfortable middle class housing of much of the rest of the area.

Hither Green Community Garden

The Community Garden dates from 2010 – cleared and maintained by volunteers from Hither Green Community Association.

North Park Farm

The Community Garden would have been part of the farmyard for North Park Farm. It was latterly farmed by the Sheppards, although the land was owned by the Earls of St Germans until the sale to Cameron Corbett in 1895 – there are already posts on both the farm itself and in the early days of the development.

There were two Sheppard brothers both of whom had houses – one of the farm houses remains at the junction of Hither Green Lane and Duncrievie Roads (see above) – along with their long term farm manager William Fry, who lived in the original farm building around the Community Garden..

The shops (see below) were developed by Corbett early in the development – there was no pub as Corbett was a strict teetotaller. There was a beer house (licenced to sell beer but not wines or spirits) nearer the station in area demolished by the V-1.

There was a small stream which I have called North Park Ditch which ran through the farm – it is visible in the Hither Green Nature Reserve and was a tributary of Hither Green Ditch, which joins the Quaggy between Manor Lane and Longhurst Road.

The Old Station

The original entrance to the station was where Saravia Court , a block of housing association flats built around 2013, is now situated – it is named after the original name for Springbank Road. The station buildings lasted until around 1974, when the booking hall was moved to its current location at platform 4½. The site was used by timber merchants for many years.

The only remnants of the former station are the stationmaster’s house, 69 Springbank Road and the gate pillars to the former station entrance

Park Fever Hospital

This was the site of two of Hither Green’s larger houses – Hither Green Lodge and Wilderness House, these were sold to a private developer in the early 1890s and then onto the Metropolitan Board of Works who built the hospital after much local opposition.

Despite the 1896 signs, the hospital opened in 1897, it went through variety of guises including fever, paediatrics, geriatrics in its century of use. The site was redeveloped for housing after the hospital closed in 1997. There is a specific post on the the hospital and the housing before and after it in Running Past in early 2018.

Opposite the hospital in Hither Green Lane was the childhood home of Miss Read – she was a popular writer of rural fiction in the mid 20th century, who covered her time there in the first volume of her memoirs.

The Green of Hither Green, the area’s small bit of common land was at the junction of Hither Green and George Lanes and was enclosed around 1810,

Roughly the same location was the ‘home’ to Rumburgh (other spellings are available) a settlement that seems to have died out as a result of the Black Death in the mid 14th century – this was covered a while ago in the blog.

Park Cinema opened in 1913 with a capacity of 500, it is one of several lost cinemas in the area. It closed its doors in 1959 and was vacant for many years – it has gone through several recent uses including a chandler – Sailsports, a soft play venue Kids’ Korner and latterly another alliteration, Carpet Corner.

Its days seem numbered as a building as after several unsuccessful attempts to demolish and turn into flats – planning permission was granted in September 2017 after an appeal against a refusal by Lewisham Council.

Beacon Road/Hither Green Lane

The Café of Good Hope is a recent addition to the Hither Green Lane, part of the Jimmy Mizen Foundation – Jimmy was murdered on Burnt Ash Road on 10 May 2008. The charity works with schools all over the United Kingdom, where Margaret and Barry Mizen share Jimmy’s story and help young people make their local communities safer, so they can feel safe when walking home.

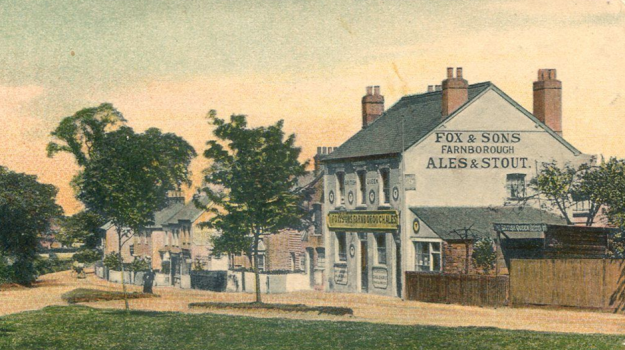

The Fox and Sons ‘ghost sign’ is next door to the Café. Ghost signs are painted advertising signs, they are not meant to be permanent – although were to last much longer than their modern day counterparts. The urban landscape used to be full of them but most have been lost – either to modern advertising, being painted over or the buildings themselves being demolished lost. There are still quite a few locally – the best local ‘collection’ is around Sandhurst Market at the other end of Corbett estate. They can be

This was very briefly an off licence, there is a photo of it but it didn’t seem to last long enough to make local directories. There is much more on the brewery behind the ghost sign in a post here.

The Pillar Box on the corner of Beacon Road may look ordinary but it was attacked by suffragettes in 1913 – it was one of many similar attacks by Lewisham’s militant WSPU branch.

St. Swithun’s Church

The church building dates from 1904, although the now church hall was used as a church from 1884. Both were designed by Ernest Newton who also designed the Baring Hall, the original Church of The Good Shepherd and Lochaber Hall. Gladys Cooper, the actress was baptised here.

Perhaps the biggest surprise with St Swithun’s (pictured above) – is that it is still here. So many of the local churches were lost in World War Two – the Methodist Church at the junction of Hither Green Lane and Wellmeadow Road, the original church of The Good Shepherd, Christ Church on Lee Park and Holy Trinity on Glenton Road.

Merbury Close

Merbury Close was developed as a sheltered scheme for the elderly in 1986. Before that it had been a nursery – the last remnant of something that this end of Hither Green had several of – the best known – run Lewisham Nursery, run in its later years by Willmott and Chaundy, which finally closed in 1860.

Bullseye or Japes Cottage – (pictured above) was on the corner of Harvard Road and Hither Green Lane – it was the gardener’s cottage for one of the larger houses on Hither Green Lane – the inappropriately named, in terms of size, Laurel Cottage.

Spotted Cow – one of the older pubs in the area, the name referring to its rural past; it closed around 2007 and was converted into flats by L&Q Housing Trust, the block at the side is the name of one of its former Chairs.

Monument Gardens

From the 1820s to 1940s this was ‘home’ to Camps Hill House, an impressive large house which was built in the 1820s for the brick maker Henry Lee – it is pictured below (source eBay October 2016) . It was demolished post-war for what initially called the Heather Grove estate. There is a much fuller history of both the estate and its predecessor in a blog post from 2016.

The monument on the grass is something of a mystery – it is dated 1721, well before Campshill House was built – it is rumoured to memorial to an animal – it isn’t marked on Victorian Ordnance maps, although seems to have been there from the mid-19th century.

Nightingale Grove

This used to be called Glenview Road and was the location of one of the biggest local losses of life during World War 1 – a large bomb was dropped by a Zeppelin in the ‘silent’ raid on the night of 19/20 October 1917. There were 15 deaths, including 10 children, two families were decimated – the Kinsgtons and the Millgates. The attack was covered in an early post in Running Past, as was its fictional retelling by Henry Williamson, better known for writing ‘Tarka the Otter.’

Hansbury’s (formerly the Sir David Brewster)

When this post was first written this was one of the more depressing sites (or sights) on the walk – a rapidly decaying former pub,. While it has been converted into flats, the bar remains closed. It was once one of half a dozen Hither Green boozers, despite Archibald Cameron Corbett preventing them on the former North Park Farm. Hither Green now has just one pub, the Station Hotel along with the Park Fever beer and chocolate shop opposite on Staplehurst Road which offers some limited seating and the new Bob’s on Hither Green Lane. A 2016 blog post tells the story of the pub.

There was an attempt to build a pub in the late 1870s in Ennersdale Road, however, there were two rival builders and they seemed to expect the magistrates to decide on which one to allow. In the end neither happened (1).

Dermody Gardens

The path over the railway to here used to be called Hocum Pocum Lane (covered a while ago in Running Past), it can be followed back to St Mary’s and beyond towards Nunhead and continues down the hill over a long established bridge over the Quaggy and then north along Weardale Road to join Lee High Road by Dirty South (formerly the Rose of Lee). It was renamed Dermody Road after an alcoholic Irish poet in the 1870s – Thomas Dermody (below) is buried at St Mary’s and there is something on his short life here.

Towards Lewisham the street layout evolved in the early 1870, the area was certainly included within the Lewisham Nursery of Wilmott and Chaundy who grew Wisteria amongst other plants, although the name of the road may predate the nursery. The area beyond this, towards Lewisham, was developed as the College Park Estate in the 1860s.

The Holly Tree closed in 2017 and, like its neighbour over the railway, while the upper floors are used as flats the doors tot eh bar remain firmly shut.

Manor Park

This was a pig farm before being turned into a park in the 1960s, although it was once of Lewisham’s more neglected parks until a major upgrade in 2007 with Heritage and Environment Agency funding the river was opened up park and the park re-planted to encourage wildlife. There are Running Past posts on both the Park and the Quaggy at this point.

While going through Manor Park is a pleasant detour – we will only see the backs of the houses of Leaahurst Road. Large chunks of this end of the street, particularity on the western side were destroyed during World War 2. The bomb sites were searched extensively during a notorious 1943 child murder investigation – the murderer was Patrick Kingston, a surviving member of the family almost wiped out in the Zeppelin attack.

Leahurst Road was also home to one of Hither Green’s once famous residents – the early Channel swimmer, Hilda ‘Laddie’ Sharp (pictured above).

Staplehurst Road

The Shops were built in the early 20th century, a little later than those in Springbank Road, the dates are marked in several places as one of the original ‘Parades’ – the sign for Station Parade is still there (above the Blue Marlin Fish Bar). The nature of the shops has changed significantly – although mainly in the period since World War 2. There is more on this in a blog post, including Hither Green’s Disney store.

The Station Hotel was built by the Dedman family who had previously run both the Old and New Tigers Head pubs at Lee Green and opened around 1907. It is now Hither Green’s only pub.

The Old Biscuit Factory is a new housing development from around 2013, the site including the building now used by Sainsbury’s was originally a very short-lived cinema, the Globe – which lasted from 1913 until 1915, before being ‘home’ to Chiltonian Biscuits.

The area around Staplehurst Road suffered badly in a World War 1 air raid – two 50 kg and two 100 kg bombs were dropped by German Gotha aircraft and fell close to 187 Leahurst Road, damaging 19 shops and 63 homes, the railway line. Two soldier lost their lives and six were injured on the evening of 19 May 1918. Unlike the World War Two attacks, there seems little evidence there now of the bombing. There was more significant damage and a lot more deaths in Sydenham in the same raid.

World War 2 damage is a little more obvious in Fernhurst Road, there was a small terrace built by the local firm W. J. Scudamore, which was hit by a V-1 rocket in June 1944. Prefabs were built there immediately after the war, with the present bungalows following in the late 1950s or early 1960s.

–

If you want to do the walk physically rather than electronically ….

It is about 1.8 miles long and all on footpaths, it seems fine for buggies and wheelchairs apart from one very narrow, steep uneven section on Dermody Road (although it is better on the opposite side of the road).

Toilets – the only ones on the route are in Manor Park, although they are only open when the café is.

Refreshments – several places either side of the station, along with the Café of Good Hope on Hither Green Lane and the Lewisham Arts Café in Manor Park

Public transport (as of May 2018) – there is a bus map here, and rail journey can be planned from here.

Notes

- Kentish Mercury 04 October 1879

Picture Credits

- The postcards and drawing of Campshill House are all from e Bay between January 2015 and January 2018

- The painting of Japes Cottage is ©Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre, on a non-commercial licence through Art UK

- The Ordnance Survey map is on a Creative Commons via the National Library of Scotland

- The photograph of the destruction of Glenview Road in the ‘silent’ Zeppelin raid is on a Creative Commons via Wikipedia

- The photograph of the Sir David Brewster (Hansbury’s) is from the information boards at Hither Green Station.

- The picture of Thomas Dermody comes from an information board at St Mary’s church

- The photographs of Hilda Sharp – left photo source, right photo Times [London, England] 25 Aug. 1928: 14. The Times Digital Archive