In an area bounded by Manor Lane, the railway between Hither Green and Holme Lacey Road there was once a pair of cricket grounds, Granville at the Manor Lane end and Northbrook at the western end abutting Lee Public Halls. We’ll look at Northbrook now and Granville in a later post.

The land appears to have previously been on the southern (left) edge of Lee Manor Farm – the farm map below from the 1840s probably marks it as ‘C K 12.1.10’. Further to the south was Burnt Ash Farm (at the current junction of Baring and St Mildred Roads).

In the mid 1860s the railway embankments had cut through the southern end of the farm cutting off the fields and seeing several other parcels of land sold for development.

Both farms were owned by the Baring Family, at that stage headed by Thomas Baring, Baron Northbrook from 1866 and Earl of Northbrook from 1876. The title was named after a village close to their Stratton Park estate in Hampshire. As was covered a while ago, some of the family money came directly from slavery, including some slave ownership.

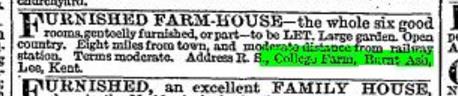

The Northbrook Cricket club seems to have been founded in 1871 by two relatively wealthy locals of mid Victorian suburbia – William Willis and William Marks (1). The latter was born in 1822 and was a Silk Merchant who lived at 30 Southbrook Road (also referred to as The Cottage) in the 1881 and 1891 censuses but had probably moved there in 1871.

The other founder was William Willis QC (pictured), who was a barrister from Bedfordshire living at 4 Handen Road in 1871, 12 Northbrook Road in 1881 and 1891, he moved to the Elms at the corner of Belmont Grove and Belmont Hill during the 1890s (2) and in Belmont Park by 1911. Willis was also a Liberal politician and MP for Colchester from 1885 until his death in 1911.

Unsurprisingly, given the name of the club, its President was Lord Northbrook (3) and the ground was imaginatively named Lord Northbrook’s Ground (4).

It was a club with a vision of success who employed a professional in its early years – the Kent player Henry Palser (5). He seems to have been a local man who was born in 1841, his father had been ‘Beadle of Lee Church’ in 1851. Palser had an intermittent career as a professional around the country over the next couple of decades; out of season, he worked as a bricklayer – he was living in Court Hill Road in Hither Green in 1881.

In the local press there wasn’t that much coverage of the club, mentions only seeming to mention fundraisers often at Lee Public Halls, next door, at least until it became a laundry. The Royal Hand Bell Ringers and Glee Singers featured in early 1880 (6). They also covered annual dinners and the speeches at them – 1878’s noted a good season winning 16/28 matches drawing 8 and losing 4; the batting averages were topped by a Mr Cole at 41 which he won a bat for at the annual dinner (7).

From the early 1880s there began to be extensive coverage of their games, or at least the scorecards in a Victorian newspaper called ‘Cricket.’ Oddly while batting averages were published, bowling ones weren’t. The matches seemed to be friendlies, or at least no league tables were produced. There is no intention here to do a complete season by season history of the club, it would be repetitive and probably not that interesting; instead we will look at a season every few years.

1883 was their 13th season and it was noted as being ‘successful and satisfactory.’ Matches played that season included their next door neighbours Granville, Sidcup, Burlington, Addiscombe, Old Charlton who played in Charlton Park, Lausanne, Islington Albion, Eltham (at Chapel Farm – now Coldharbour Leisure Centre), Orpington, Hampton Wick, Pallingswick (close to Hammersmith) and Croydon.

Thirty six matches were played that summer of which 15 were won, 8 lost – of the 13 drawn games, 8 were in the favour of the men from Lee. The batting averages were headed by a W J Smith on 22.13 (8).

By 1889 the opponents were similar although matches had extended down into Kent, with matches against Gravesend and Greenhithe added. There were 46 matches played 15 won, 12 lost, 12 drawn and 7 abandoned in the wetter summer. The batting averages were headed by P W G Stuart on 52.7 (9) – he was probably army Lieutenant, Pascoe Stuart who had been born in Woolwich but had moved away from the area by 1891. Heading the bowling averages was E D J Mitchell who lived just around the corner in Birch Grove, just over the road from E Nesbit of Railway Children fame.

In the late 19th century, Lee was a prosperous area on the edge of the city and those who played for the team in that era reflected that. They included that season Thomas Blenkiron (10) a silk merchant who live on Burnt Ash Hill who had family links to Horn Park Farm – the house they lived in was called Horn Park.

1893 started badly for the club with the pavilion being destroyed by fire in January the cause was not clear (11). The rebuilding was incredibly rapid, with a new ‘half timbered structure with three gables’ built by Kennard Brothers of Lewisham Bridge and opened in late April ahead of the new season (12). The location was mid-way along what is now Holme Lacey Road (below).

Reporting became a lot more reduced during the 1890s, the reasons for this aren’t that clear although it may be because the nature of the Cricket newspaper may well have changed. In the 1880s smaller clubs like Northbrook were able to pay to have their scorecards covered, this didn’t happen any more in the final decade of the century with mentions reducing to, at best, a couple of sentences. 1899 was a poor season for the club, matches includes matches against Goldsmiths’ Institute – the home away away games involved heavy defeats; a winning draw against Dulwich and a draw in the return fixture at Burbage Road, a losing draw against the London and Westminster Bank, defeats to Panther, Charlton Park and Forest Hill (13).

The number of mentions got further and further between in the 20th century, with only a handful of reports each year. There were a few more mentions in 1912 which seems to have been a relatively successful one for the club. There was a winning draw against Albemarle and Friern Barnet in and victories against Addiscombe and Crofton Park in May and June respectively – A W Fish scored 50s in both games and probably his brother, HD was a centurion in June against Hertford, with Mansel-Smith a centurion against Bromley Town a few days earlier.

There was a comfortable victory against Derrick Wanderers in Manor Way in Blackheath (pictured above in 2020); the ground is still open space but is now abandoned and fenced off, owned by a development company hoping no doubt for a planning law changes that will allow them to develop the site.

In January 1914 the Northbrook Cricket Club pavilion was burned down again. While the Lewisham WSPU branch never claimed responsibility, that week’s ‘The Suffragette’ implied it was the their work the headline noting. ‘Fires and Bombs as Answer to Forcible Feeding’ and having a report on the fire below (bottom right hand corner). The national press was a little more circumspect about naming the culprit though and no one was ever charged with the arson.

It isn’t clear what happened to the club after their 15 minutes of infamy in 1914. While it is possible that it continued for the rest of the 1914 season, it is likely that World War One brought cricket to a halt there most sport – as we saw with Catford Southend football club.

By 1924, the landowners, presumably still the Northbrooks, had cashed in on the value of the land and sold it. The Northbrook ‘square’ was covered by the Chiltonian Biscuit factory which had moved on from Staplehurst Road. Today, it is the home of the Chiltonian Industrial Estate, pictured below. The pavilion and southern edge of the outfield was covered at around the same time by the houses of Holme Lacey Road, built by W J Scudamore – pictured earlier in the post.

Notes

- Kentish Mercury 28 April 1893

- Neil Rhind (2020) Blackheath and its Environs, Volume 3 p518

- Kentish Mercury 11 January 1873

- Sporting Life 23 September 1871

- Kentish Mercury 27 May 1871

- Kentish Mercury 24 January 1880

- Kentish Mercury 23 November 1878

- Cricket 20 September 1883

- Cricket 26 September 1889

- Cricket 26 September 1889

- Reynolds’s Newspaper 8 January 1893

- Kentish Mercury 28 April 1893

- Cricket 1899 various dates

Credits

- The 1843 map of Lee Manor Farm and the picture of the Chiltonian Biscuit Factory are part of the collection of Lewisham Archives, they are used with their permission and remain their copyright;

- The picture of William Willis is via WikiTree on a Creative Commons

- The map showing the location of the ground is on a non-commercial licence via the National Library of Scotland

- Census and related data comes from Find My Past