There is a postcard that appears from time to time on Lewisham Facebook reminiscence groups and for sale on eBay of a small house set back from the road with the label Burnt Ash Hill. In the former locations, it often causes consternation as there are no obvious current or even recent landmarks. The house was Wood Cottage and this post seeks to tell at least some of its story, and more particularly the nurseries that it was linked to.

The cottage probably dates from the 1870s and was broadly where the Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady of Lourdes now stands (pictured below) – midway between Lee Station and what is now the South Circular of St Mildred’s Road and Westhorne Avenue.

The origin of the name is unclear, although the most likley scenario is after one of the Wood family who farmed the neighbouring Horn Park Farm who may have farmed the land for a brief period in the 1860s.

The firm running the nursery for much of its life was Maller and Sons. It was set up by Benjamin Maller, a gardener who hailed from Surrey (Sussex in some censuses). Born in 1823, he was living with wife Mary and daughter Mary at Belmont Lodge in 1851 – which was attached to Belmont a large house on what is now Belmont Hill, where he was the gardener.

In the 1861 census, Maller had moved just down the hill and was listed at 5 Granville Terrace, later it was to have the address 61 Lewisham High Street. It is now part of the Lewisham police station site, but before that, became part of the Chiesmans empire. Maller was listed as a ‘Nurseryman employing two boys’ in the census. Long and Lazy Lewisham which is covering the history of the High Street, notes that he had been there, trading initially with Robert Miller for around 5 years.

The partnership with Miller was short lived as was another with George Fry which ended in 1860. The next decade saw a rapid expansion, the 1871 census suggests he was employing 31 men and 6 boys.

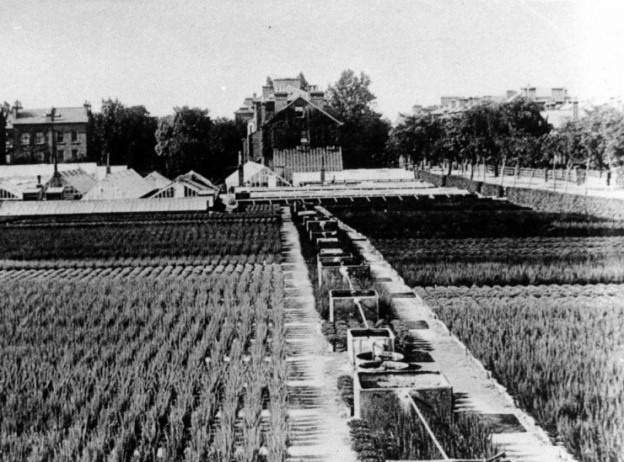

By 1881 they were listed in the census as being in Leyland Road – the numbering isn’t totally clear as the road was being developed and the house is just described as ‘The Nursery.’ This is pictured above (back middle), it was later numbered 72 and puts it now at the corner of Leyland Road and Alanthus Close. The nursery shown on an 1890s Ordnance Survey map. below, along with several other areas cultivated.

This would have been land leased from the Crown, part of the former Lee Green Farm (pictured below) which ceased operating in the1860s. While the exact geography of the farm isn’t completely clear – it seems to have been a narrow farm covering land to the east of what is now Burnt Ash Road and Hill from Lee Green to around Winn Road. Just a few hundred metres wide, it shrank rapidly as homes and shops were developed by John Pound following the arrival of the railway in Lee in 1866. Land was also temporarily lost to clay pits and brickworks just south of Lee Station and north of The Crown.

In 1881 Maller was listed as a nursery man with 30 acres employing 4 men 8 boys. The family included grown-up children Mary, Benjamin and Herbert – in the 1881 census at ‘the Nursery, Leyland Road’.

There had been of significant reduction in labour since 1871 – 31 men to just 4 over 10 years. This probably relates to the land they cultivated being rapidly lost to Victorian suburbanisation as streets like Dorville, Osberton and Leyland Roads were developed.

Benjamin died in 1884 but the business continued as B Maller and Son afterwards, with Benjamin Boden Maller in charge – living variously at 107 and 111 Burnt Ash Road (there was access to the site from Burnt Ash Road too) and 72 Leyland Road. Benjamin Boden Maller died in 1913 although his son, also Benjamin, continued for a while. However, in the 1939 Register he was listed as a Civil Servant living in Reigate.

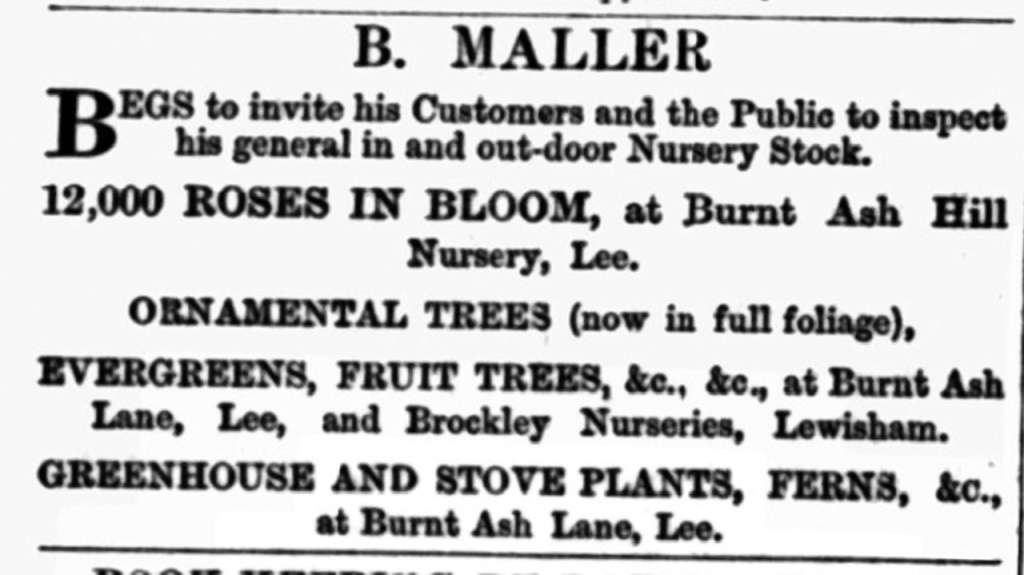

So what did they grow? In 1879 an advert in the Kentish Mecury suggested the land cultivated from Wood Cottage (Burnt Ash Hill site) was for roses. The site around Leyland Road (listed as Burnt Ash Lane) was used for trees and and shrubs as well as having greenhouse plants and other plants that needed warmth – stove plants. While they cultivated Brockely Nursery they had moved from there as the Billinghursts (see below) were there by 1880 (1),

It seems that before the end of the century there was a change in focus with a lot of plants being grown for seed – they were regualrly advertising their illustrated seed catalogue to the gardeners of south east London and beyond (2).

In the early 20th century, they would also have auctions of surplus stock in September each year. The 1910 sale included 20,000 winter blooming heaths, gorse, winter aconites, ferns and palms (3).

The land that is now part of Alanthus Close seems to have remained with the Mallers until around the mid 1920s. On Burnt Ash Hill they will have added the land of the former brickworks less the frontage onto Burnt Ash Hill and a development next to The Crown centring on Corona Road. This will have been an extension of the land cultivated from Wood Cottage.

It seems that the land was split three n the mid to late 1920s when the Mallers left. There were different names at 107 Burnt Ash Road (May Scotland), 111 Burnt Ash Road (George Friend Billinghurst) and Norris Buttle at Wood Cottage.

May Clark Scotland was appropriately Scottish, born in Perth, she was running a florists at 111 Lewisham High Street by 1911, the name over the door was Alexander Scotland.

George Billinghurst was born around 1871 and seems to have spent his early years in Eliot Place in Blackheath, his father Friend Billinghurst was also a gardener. There is no obvious link to the more well known Blackheath Billinghurst family, which included disabled suffragette (Rosa) May. They seem to have cultivated Brockley Nursery for a while (4), after the Mallers moved out, but family moved on to Croydon. By 1891 George was listed as a gardener, a decade later a florist and by 1911 a nurseryman living in Annerley Road.

Norris Buttle was living at 172 Ennersdale Road in 1901 and at 31 Leahurst Road in 1911 (these were probably the same house as the Ennersdale originally dog-legged around) – he was listed as a gardener then nursery gardener.

With all three of them, details beyond 1911 proved difficult to work out. Certainly none of them were at 72 Leyland Road – it was empty in 1939 as were 8 out of 10 the houses of that end side of the street going southwards. It was a different picture going northwards.

Time was running out for the nurseries too, the land cultivated from Wood Cottage was lost in the 1930s as leases ran out and the Crown sold the land for development. The land behind Wood Cottage was lost to the Woodstock Estate of Woodyates and Pitfold Roads. Further south, the new South Circular and the developments around Horncastle and Kingshurst Roads, pictured above, further depleted the land. The Cottage itself was lost to the new Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady of Lourdes – the church had acquired the land in 1936.

The land sandwiched between Leyland and Burnt Ash gradually was encroached upon with development at the southern end of Leyland Road although there were memories of roses being grown until the early 1960s when many Crown Estate leases ended.

And finally, while no longer cultivated, there is a small piece of undeveloped land where the nursery was – the green space to the south of Alanthus Close. On some satellite images of the area in drought conditions show rectangles, probably the ghosts of greenhouses past – a little less clear than the prefabs around Hilly Fields.

,

Notes

- Kentish Mercury 16 August 1879

- Kentish Mercury 09 February 1894

- Kentish Mercury 02 September 1910

- Croydon Guardian and Surrey County Gazette 3 July 1880

Credits

- Census and related data come from Find My Past (subscription required)

- Kelly’s Directories were accessed via a combination of Southwark and Lewisham Archives, with the reference to Lewisham High Street via the on-line collection of the University of Leicester

- The postcard of Wood Cottage is via eBay in January 2021

- The drawing of Lee Green Farm is from the information board at Lee Green

- The photograph of the land between Burnt Ash Road and Leyland Road is part of the collection of Lewisham Archives, it remains their copyright and is used with their permission.

- The Ordnance Survey map is part of the collections of the National Library of Scotland – it is used here on a non-commercial licence

- The satellite image of Alanthus Close is via Apple Maps