During the 2020 Coronavirus lockdown, Running Past has been following the boundary of Victorian Lee before it was subsumed into Lewisham at the end of the Victorian era, aided only by a Second Edition Ordnance Survey map. We have so far wandered, in stages, initially from Lee Green to Winn Road, appropriately passing Corona Road en route; the second stage took us through Grove Park, crossing the never built Ringway; then through Marvels and Elmstead Woods and a Borough of Deptford Cemetery; and in the previous instalment through Chinbrook Meadows appropriately following Border Ditch. We pick up the 1893 Lee – Lewisham boundary on what is now Downham Way – the most southerly of the red dots on the map below.

The Downham estate was built by the London County Council (LCC) in the late 1920s and early 1930s on compulsorily purchased farm land. On this side of the estate included what was probably the last outpost of the land owned by the Baring family, Shroffold Farm, pictured later in the post. We will probably return to the farm at some stage in the future. However, the farm was part of the Manor of Lee bought by Sir Francis Baring, later Baron Northbrook, the purchase of which was at least partially funded by both financing of slave owning operations as well as some direct ownership on enslaved people. While the Barings dispensed largesse to the locals in their latter years, their ability to do this was based, in part at least, on the enslavement of African men, women and children in Montego Bay in Jamaica at the end of the 18th century.

The Downham estate was built by the London County Council (LCC) in the late 1920s and early 1930s on compulsorily purchased farm land. On this side of the estate included what was probably the last outpost of the land owned by the Baring family, Shroffold Farm, pictured later in the post. We will probably return to the farm at some stage in the future. However, the farm was part of the Manor of Lee bought by Sir Francis Baring, later Baron Northbrook, the purchase of which was at least partially funded by both financing of slave owning operations as well as some direct ownership on enslaved people. While the Barings dispensed largesse to the locals in their latter years, their ability to do this was based, in part at least, on the enslavement of African men, women and children in Montego Bay in Jamaica at the end of the 18th century.

We’d split our circuit of Lee at the top of what was described in a 1790 map as ‘Mount Misery’, better known these days as Downham Way (the most southerly dot on the map). There was a lot of ‘misery’ in the area in that era. South Park farm, which was to become North Park – a little further down the hill in our broad direction of travel was a farm that for a while was known as Longmisery.

The reason for the split in the post at Mount Misery was that the boundary in 1893 had changed soon after the brow of the ‘Mount’ from field edge to stream at the boundary.

Before leaving this point, it is worth remembering that at the time the Ordnance Survey cartographers surveyed the area they would have had an undisturbed view almost to the north of the parish and St Margaret’s Church. Certainly this was what the local Victorian historian, FH Hart, noted in the early 1880s when following the boundary from this point.

The stream is Hither Green Ditch; a stream that Running Past followed a while ago which has several sources. The nomenclature ‘Ditch’ is used quite a lot within the Quaggy catchment, it shouldn’t be seen as belittling or derogatory it is just the way smaller streams are described – the 1893 boundary of also followed, Grove Park Ditch and Border Ditch, with Milk Street and Pett’s Wood Ditches further upstream.

This branch of Hither Green Ditch seems to have emerged somewhere around Ivorydown, south and above Downham Way. It merges with the 1893 Lee – Lewisham boundary just north of the street named after the farm, Shroffold. The merged boundary and stream followed the middle of Bedivere Road.

The section that the Lee-Lewisham boundary initially followed, is one of the sections of Hither Green Ditch that is barely perceptible on the ground, although the contours are clear on early 1:25,000 Ordnance Survey maps, if not current ones. Whether this part of the stream was actually flowing in 1893 is, at best, debatable, water tables had declined after the end of the Little Ice Age, the last really cold winter was in 1814 – with extensive flooding around the parish of Lee when there was a thaw.

The boundary and stream followed the edge of a small piece of woodland in 1893 which is now an area bordered by Pendragon, Ballamore and Reigate Roads. There is an attractive U shaped portion of the latter, where council surveyors struggled with dampness from the hidden Ditch.

The post war 1:25,000 Ordnance Survey map, notes a flow at around the point of Railway Children Walk, an homage (or a homage) to E Nesbit who lived on the other side of the railway – on of at least a trio of locations within the Parish she resided in. A small detour is worth making for a view of another Lewisham Natureman stag standing proudly above the railway.

The post war 1:25,000 Ordnance Survey map, notes a flow at around the point of Railway Children Walk, an homage (or a homage) to E Nesbit who lived on the other side of the railway – on of at least a trio of locations within the Parish she resided in. A small detour is worth making for a view of another Lewisham Natureman stag standing proudly above the railway.

Detour made, the boundary follows Hither Green Ditch which was marked as flowing in the 1960s 1:25,000 Ordnance Survey map, so was presumably also flowing in 1893. To the west of the Ditch, and boundary, was Shroffold Farm, the farmhouse (pictured below from the 1920s) was where the mosque is now located – diagonally opposite to where the Northover/Governor General was to be built 40 years later at the junction of Verdant Lane, Northover and and Whitefoot Lane. To the east was almost certainly land belonging to Burnt Ash Farm – both sides of the boundary owned by the Northbrooks.

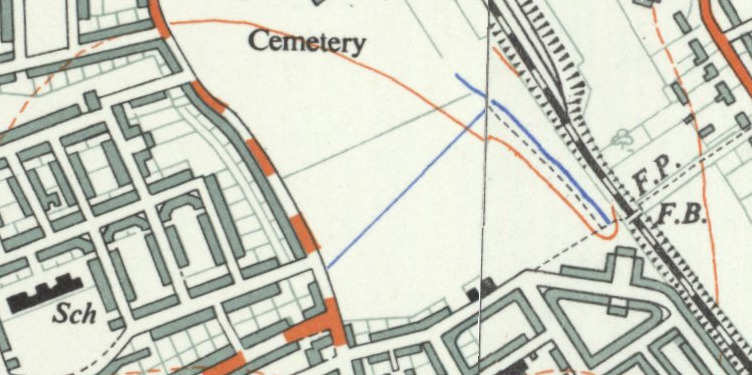

While fields in 1893, this area is now part of Hither Green Cemetery. It originally opened as Lee Cemetery in 1873 but with a much smaller size at the northern end of the current one. Like the Borough of Deptford cemetery we passed through in Grove Park, it was outside the jurisdiction it served, all on the Lewisham side of Hither Green Ditch. There are two impressive chapels, the Dissenters one (for Methodists and the the Baptists of Lee High Road and what is now Baring Road), was built by William Webster of Blackheath and was damaged during the last war and is slowly decaying.

The southerly end of what is now the cemetery had changed from farm land to allotments in the early part of the 20th century. The exact timing of the expansion of the cemetery into the allotments isn’t clear, it was probably just before or just after the start of World War 2, it was showing as allotments in the 1938 surveyed Ordnance Survey map. But by the time the children who died in the awful attack on Sandhurst Road School in early 1943, were buried the area had expanded. There is a large memorial to those who perished, something covered in a blog post that marked the 75th anniversary of the bombing in 2018. The crematorium in the south east corner was opened in the 1950s.

The 1893 boundary is relatively easy to follow on the ground through the cemetery as Hither Green Ditch has left a small valley close to the Lombardy poplars that border the railway.

Just outside the cemetery in 1893 was a small hospital, Oak Cottage Hospital; it had been built in 1871 by the local Board of Works for dealing with infectious diseases like smallpox and typhoid (1). It was overtaken by events in that the Metropolitan Board of Works (which covered all of London) decided to open a series of fever hospitals as a response to a major Scarlet Fever epidemic in 1892/93, the health system was unprepared and there was a severe shortage of beds. One of these was the Park Fever Hospital, later referred to as Hither Green Hospital; Oak Cottage Hospital was briefly considered as a possible alternative location (2). Oak Cottage Hospital closed soon after Park Fever opened in 1896 (3). It eventually became housing in the 1960s or 1970s.

Beyond Oak Cottage Hospital in 1893, were again fields, probably part of Shroffold Farm. On the opposite side of Verdant Lane (then Hither Green Lane) was North Park Farm, about to be ploughed under by Cameron Corbett. The Lee Lewisham boundary continued to use Hither Green Ditch which was to remain visible until the development of the Verdant Lane estate in the 1930s. This section is pictured below, probably soon after the Corbett Estate was completed around 1910.

In addition to the Ditch, there were a pair of long gone boundary markers, one was just to the north of the junction of Verdant Lane and Sandhurst Road, perhaps at the point one of the confluence of two of the branches of the Ditch; the other where it crosses St Mildreds Road – again a possible branch of the Ditch that would have been obliterated by the railway.

St Mildreds Road hadn’t existed when the Ordnance Survey cartographers had first visited in the 1860s. While the church of St Mildreds had been built in 1872, even in 1893 only homes at the Burnt Ash Hill end had been build, including another of the homes in the area of E Nesbit in Birch Grove.

The boundary went under the railway close to what was a trio of farm workers cottages for North Park Farm, which are still there at the junction of Springbank Road and Hither Green Lane.

The boundary continued to follow Hither Green Ditch – it wasn’t just a Parish boundary at this point, but a farm boundary too – on the Lewisham side, Hither Green’s North Park Farm, which was mainly on the other side of the railway and was sold at around the time that the land was surveyed and would form the Corbett Estate. On the Lee side was Lee Manor Farm, which is pictured on a 1846 map below (right to left is south to north, rather than west to east) and Hither Green Ditch which had several small bridges is at the top. There were several boundary stones and markers along what was broadly Milborough Crescent and Manor Lane. There was then a sharp turn to the east along what is now Longhurst Road.

The confluence of Hither Green Ditch with the Quaggy was in a slightly different place in 1893, then it was more or less where 49 Longhurst Road is now located; it is now around 40 metres away on a sharp corner between between Manor Park and Longhurst Road, as pictured below.

We’ll leave the boundary of Lee and Lewisham here for now following what is now the Quaggy into Lewisham in the next instalment.

This series of posts would probably not have happened without Mike Horne, he was the go to person on London’s boundary markers, he had catalogued almost all of them in a series of documents. He was always helpful, enthusiastic and patient. He died of a heart attack in March but would have loved my ‘find’ of a London County Council marker in some undergrowth on Blackheath, and would have patiently explained the details of several others he knew to me. A sad loss, there is a lovely series of tributes to him.

Notes

- Godfrey Smith (1997) Hither Green, The Forgotten Hamlet p54

- Woolwich Gazette 02 June 1893

- Smith op cit p54

Picture Credits

- The photographs of Shroffold Farm, Verdant Lane and the plan of Lee Manor Farm are from the collection of Lewisham Archives, they are used with their permission and remain their copyright

- The 1863 map is from the National Library of Scotland on a non-commercial licence