There have been several posts in Running Past on World War 2 bombings and post-war reconstruction, many of these have been around V-1 and V-2 attacks such as those on Lenham Road, Lewisham Hill, along with a pair of Hither Green ones – Nightingale Grove and Fernbrook Road. More recently Running Past has covered the attacks that happened on three nights on their 80th anniversaries – the First Night of the Blitz of the as well as the post Christmas raids on the nights of 27/28 and 29/30 December 1940. We turn our attention now to the more widespread damage on Springbank Road caused through a variety of attacks.

The level and scale of damage becomes clear when looking at the London County Council Bomb Damage Maps pictured above (1) which shows that most of the houses in the street had some form of damage. Rather than Springbank Road itself, Hither Green marshaling yards, behind the eastern side of the street, were one of the two main Luftwaffe targets in Hither Green during the Blitz, the other being the hospital (2). The damage was much greater to Springbank Road though than to the west of the railway.

Large swathes of the street were mapped as red by the London County Council surveyors – ‘seriously damaged (doubt if repairable)’ or worse. In reality, a lot more end up surviving the war than the map suggests.

The Air Raid Precautions (ARP) Service logs make for fascinating reading in terms of trying to work out what damage happened when in Hither Green and the extent of the damage. However, as we’ve seen in relation the First Night of the Blitz as well as the post-Christmas raids, recording in the log was patchy at best with some high explosive and incendiary bombs only being recorded by the Fire Brigade and others, which were dealt with by local ARP Fire Wardens, were never recorded.

On the third night of the Blitz, on 9 September 1940, it is clear that 136 Springbank Road was hit. What is less clear is whether this was a direct hit or the fallout from the bombing of the house behind at 51 Wellmeadow Road. This was the house was on the corner with Torridon Road and marked in black on the map above and was completely destroyed. This part of Wellmeadow Road was rebuilt after the War. William Brown (83) and Alice Budd (56) died at 51 Wellmeadow Road that night.

136 Springbank was less badly damaged, although it seems to have undergone some wartime or post-war rebuilding work as from the front from the variety of slightly different bricks were used. One of the inhabitants was Mary Hutcheson – it was a large house that she shared with a couple – the Gallotts. Mary was seriously injured in the bombing, although she lived for another 6 months before dying at St Alfege’s Hospital (later Greenwich) on 10 March 1941, aged 82.

Elsewhere on Springbank Road, there was some serious damage further down the street with 213 to 225 completely destroyed. The date of this bombing isn’t clear as the attacks appear not to have been recorded in the ARP log (3). Unlike 136 Springbank, no one was killed in the attack, although given the scale of the damage it would be surprising if there were no injuries. 213 to 225 (pictured above) were rebuilt as a mixture of Borough of Lewisham houses and flats after the war. On the other side of the street, there was destruction and rebuilding too, but you have to look closely to see the differences compared with the original Corbett estate homes – the brickwork around the doors and windows is different and the homes are similar to replacement houses in Wellmeadow Rod, which we’ll cover below.

Elsewhere on the eastern side, homes got away with some more limited damage; there had to be re-building work at 211; while its next-door neighbour didn’t survive, the roof, chimneys and bay wall had to be re-built at 211.

There had were several nights during December 1940, notably that of 29/30, when the area on the other side of the railway had seen 1 kg incendiary bombs raining down. Springbank Road escaped on those nights. However, three weeks earlier on the night of 8/9 December, there had been a similar attack over a slightly wider area – there were a trio of hits at just before 11:00 pm at the southerly end of Springbank Road – none of the repots had any indication of the extent of any damage or casualties. It could have been the attack that destroyed 213 to 225, as the fire services will have been overstretched that night, although incendiary damage tended to be of a much smaller scale and often put out by wardens.

V-1 doodlebug attacks started to pepper the area from 16 June 1944 – in Hither Green and neighbouring areas, during the first week there had been attacks between George Lane and Davenport Road on 16 June; Lewisham Park the same day; Lewisham Hill and Leahurst Road on 17 June and the junction of Lenham and Lampmead Roads on 22 June.

Research on the accuracy of V-1s has noted that they had ‘relatively low accuracy… compared to modern missile systems’ but that the aim of the attacks was ‘to achieve its terror and urban damage objectives’ rather than hit specific targets. So, V1 flying bomb hits on Hither Green and surrounding areas weren’t specifically targeted here. Indeed, as we have mentioned in other posts on V-1 attacks there is some evidence to suggest that false intelligence was spread back to Germany which indicated that the early V-1 flying bombs were overshooting the north west of London and latter ones were re-calibrated slightly leading to south London boroughs such as Lewisham, Woolwich and Croydon being disproportionately affected.

At around 7:15 in the morning of Friday 23 June 1944 Hither Green had a double hit either site of the railway – Fernbrook Road, which Running Past covered a while ago and Springbank Road; where the block of Corbett Estate housing of 104 to 116 Springbank Road was either destroyed or had to be demolished along with the similar houses behind in 27-37 Wellmeadow Road – the scale of debris blocked Springbank Road for a while.

It was perhaps surprising that only one person died, Annie Taylor (57) who was visiting 110 Springbank from her home at 121 Brightfield Road – Annie was a widow and had lived with her son and daughter in law. There were several reports of the level of injuries in the ARP log – which were thought at one point to be as high as 25, although final tally seemed to be 14.

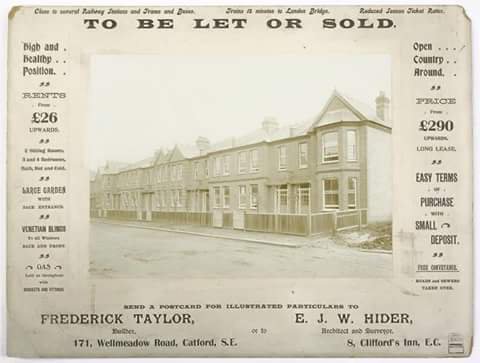

We don’t know the identity of those injured but from the 1939 Register we can work out something about the people who were living in 104 to 116 Springbank Road and the houses behind in 27-37 Wellmeadow Road. Before doing that, it is worth remembering that the houses had been built as suburbia for the middle classes of Victorian and Edwardian London. The houses in Springbank Road were some of the later ones built on the Corbett Estate and didn’t appear in the 1901 census, but were in the 1911 edition. The difference between Springbank Road and nearby streets such as Ardmere Road in 1911 is dramatic. The latter had been built as working class housing with the small houses generally shared between two households with income coming from manual work. In Wellmeadow and Springbank they were office and sales jobs – with several commercial salesmen and clerks along with a cashier and an accountant. There were no manual jobs apart from servants in 3 of the 11 houses. Despite the large houses, large households were rare – it was a very different life to that in Ardmere Road.

By the time the 1939 Register was taken, both streets had changed a lot – the middle class had moved out and both Wellmeadow and Springbank Roads were homes to manual workers, the only exceptions being the adult Spurrell sisters at 112 Springbank – which included Edith who was a Ledger Clerk at a bookshop but also worked as an ARP First Aider. They were more well-to-do than their counterparts in Ardmere Road and Woodlands Street, the households were smaller and there was less sharing. Only 108 Springbank and 31 Wellmeadow were split between more than one household. None of the men (or women) were able to claim the ‘Heavy Work’ supplement which entitled larger rations.

The housing built after the war on both Springbank and Wellmeadow sides of the site seems to have been private sector; this is unlike many of the other V-1 attacks that Running Past has covered – Hither Green Station, Lenham/Lampmead Road, Lewisham Hill and Fernbrook Road where it was homes built for the local authority. On Springbank Road 104 to 116 (pictured above) were re-built, initially as houses although most have been converted into flats. Based on Land Registry data, most remain in the private sector although one has been subsequently acquired a housing association. It was very different in Wellmeadow where the houses seem to have been built almost as 1950s versions of their predecessors – again all but one are privately owned, with one has been bought and converted into flats by a housing association.

Notes

- Laurence Ward (2015) The London County Council Bomb Damage Maps 1939-1945 – permission has been given by the copyright owners of the map, the London Metropolitan Archives to use the image here

- Godfrey Smith (1997) Hither Green, The Forgotten Hamlet p63

- It is possible that some mentions were missed when scanning through the very fragile records

Data Sources

- The ARP records are via Lewisham Archives

- 1939 Register data is via Find My Past – subscription required

- Land Registry data is via Nimbus Maps – registration required.

- The photograph of 136 Springbank Road is via Streeview