Ardmere Road in Hither Green is a quiet residential street of smaller Victorian terraced houses with some post Second World War bomb damage replacement homes; it is older than the homes to the south and predates the arrival of the station by around 15 years.

It was unusual in the area in that when Charles Booth’s researcher Ernest Aves included it on his 1899 walk which was mapping poverty in late Victorian London it was coloured ‘dark blue’, one up from the lowest class. He described Ardmere Road as

One of the fuller streets, shoddy building, two families the rule.

Charles Booth conducted an ‘Inquiry into Life and Labour in London’ between 1886 and 1903 – for much of the city he produced wonderfully detailed maps coloured on the basis of income and the social class of its inhabitants. His assessment was based on walks carried out either himself or through a team of social investigators, like Aves, often with clergymen or the police, listening, observing what he saw and talking to people he met on the road. The observations were part of a longer walk by Ernest Aves that took in much of the Corbett estate which was being built. The extract of the map below is available from London School of Economics as a Creative Commons.

![]() Hither Green had been just a series of large houses along what is now Hither Green Lane and North Park Farm when the railway navvies carved the route through the area in the 1860s. There were little bits of development around the edges of the area in the next decade – with roads like Courthill Road emerging. The houses in Ardmere Road, along with the those in the neighbouring Maythorne Cottages were much smaller though and were built before the school in Beacon Road – the site for which was bought in 1881 (1)

Hither Green had been just a series of large houses along what is now Hither Green Lane and North Park Farm when the railway navvies carved the route through the area in the 1860s. There were little bits of development around the edges of the area in the next decade – with roads like Courthill Road emerging. The houses in Ardmere Road, along with the those in the neighbouring Maythorne Cottages were much smaller though and were built before the school in Beacon Road – the site for which was bought in 1881 (1)

So was Aves right about the street? The 1901 census was carried out a couple of years after Aves visited Hither Green, so the street was unlikely to have changed that much. The census showed two households in each house were the just the majority, in 16/30 houses – with an average of 7.8 people living in the small three bedroom houses – the highest being 12. There were a couple of shops – a grocer at 18 and an off-licence beer shop at 17.

All were manual labourers except for the Police Constable at 9, and you could probably make the case for PC Davies being a manual worker too. A disproportionate number of the men worked in the building trade – some of these will have worked for Cameron Corbett’s contractors in the development of the Corbett Estate. While Corbett initially rented out some of the smaller houses on his estate to building workers – notably in Sandhurst Road – this probably wasn’t sufficient.

A lot of the women worked – 8 were laundresses taking in washing for the wealthier households in the streets around – although some may have worked at laundries; there were a trio of charwomen and a couple of dressmakers.

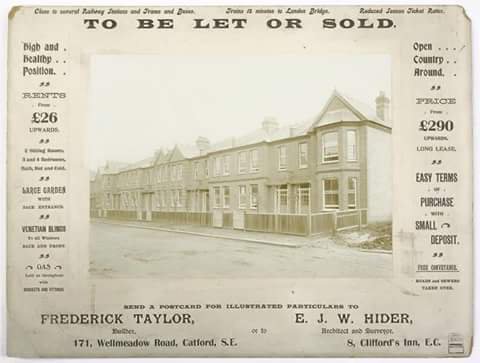

In the early years of the street rent levels were low – around five years after they were built they were being offered for rent as ‘seven roomed houses, in good locality, bay windows, forecourt, rent 7s per week’ – that’s 35p for those without pre-decimal knowledge (2).

Rent levels seem to have slightly reduced in the next decade – 21-32 were sold in 1894 as the owner was bankrupt – a couple of hundred properties across London were sold at the same time. The advertised rent level at Ardmere Road would have averaged 31p a week (3).

A decade later, when there were further sales, rents had gone up significantly – at 21, 22 and 23 they were 9/- (45p), 8/6d and 9/- respectively. Whereas at 4 and 5 they were more expensive at 10/-. A few hundred metres away on similar sized houses on Ennersdale Road houses were offered at 13/- a week (4). The rent increases probably related to the opening of the station at Hither Green. 21 – 23 were sold again in 1907 – rents hadn’t changed though (5).

The tenanted value of the houses was around £140 – based on the sale of an unspecified pair of properties in 1908 (6). The trio of 21-23 Ardmere Road homes was again sold just before the outbreak of World War 1 – rent levels had declined slightly to 8/6d. The freeholds of most of the street were sold at the same time (7).

Perhaps part of the reason for the frequent changing of hands were difficulties in collecting the rent. There was a case of claim and counterclaim at the Police Court in 1897. One of the tenants was alleged to have assaulted the rent collector by hitting him with a chair. The rent collector, who described himself a clergyman of the Church of England, was witnessed to having used language and behaviour that would not been heard coming from the pulpit – calling the tenant a ‘dirty cow’ and then attempting to strangle her after she only offered him 10/- towards rent (and presumably arrears). Both cases thrown out by the Police Court (8).

There was lots of low level crime relating to the street – the O’Connor brothers at 30 appeared several times in court. Hugh was described as a ‘bad lad’ after stealing a ‘whip from a trap’ in Ardmere Road in 1890 (9). He was again in court in 1894 after stealing tinned fruit from a shop on Ennersdale Road (10); younger brother Michael was convicted of stealing from orchard in Nightingale Grove and was remanded for a week the following year (11).

There were a couple of dozen similar reports of theft in the local press between the early 1880s and the outbreak of the Great War. While not attempting to excuse them, most seem to have been born out of the grinding poverty that seems to have existed on the street. A laundress at 23 was remanded for pawning various clothes which belonged to a resident of the nearby, wealthy College Park estate (12).

There were thefts of a marrow in 1886 (13) and milk in 1887 (14), and several occasions of stealing lead piping including from empty houses on the street which belonged to the Finsbury Building Society the same year (15).

There were, of course, alcohol related convictions too, the father and son Lustys, from 21 were together charged with being drunk and disorderly in 1887 (16).

There was an off-licence at 17 run initially by Lewis White, who held the licence from 1879 to 1897. He was also a ‘General Dealer’ and had several brushes with the law, including allowing purchasers to drink outside the off-licence in 1884 (17). He was charged with selling alcohol outside permitted hours in early 1887 (18).

The last event seems have led to the bench refusing to grant him a new licence, so in the end it was transferred to William Barrett (19). Barrett seems to have tried to extend to 18 in 1898 and obtain a full beer house licence, unsuccessfully on this occasion (20). Oddly the Ordnance Survey, incorrectly showed the 17 as a public house when surveyed in the 1890s. Perhaps that’s how William Barrett’s tenure there appeared to the cartographers, it wasn’t though what the magistrates had approved though! (21)

We will leave Ardmere Road early in the 20th century, the second part of the post returns to the street in 1939 and looks at the changes to the street since then.

Notes

- 29 October 1881 – Woolwich Gazette – London, London, England

- 26 September 1884 – Kentish Mercury – London, London, England

- 27 October 1894 – South London Press – London, London, England

- 13 May 1904 – Kentish Mercury – London, London, England

- 17 May 1907 – Kentish Mercury – London, London, England

- 20 November 1908 – Kentish Mercury – London, London, England

- 07 March 1914 – Middlesex Chronicle – London, London, England

- 28 August 1897 – South London Press – London, London, England

- 26 September 1890 – Kentish Mercury – London, London, England

- 20 April 1894 – Kentish Mercury – London, London, England

- 30 August 1895 – Kentish Mercury – London, London, England

- 6 October 1880 – Woolwich Gazette – London, London, England

- 08 October 1886 – Kentish Mercury – London, London, England

- 16 December 1887 – Woolwich Gazette – London, London, England

- 18 February 1887 – Kentish Mercury – London, London, England

- 25 March 1887 – Kentish Mercury – London

- 06 September 1884 – Kentish Independent – London, London, England

- 14 January 1887 – Woolwich Gazette – London, London, England

- 01 October 1897 – Woolwich Gazette – London, London, England

- 09 September 1898 – Woolwich Gazette – London, London, England

- On a Creative Commons via the National Library of Scotland

Charles Booth’s map is available from London School of Economics as a Creative Commons.

Notes re FMD