Last year Running Past looked at two of the most intense nights of World War Two bombing in Lee on the 27 and 29 December 1940. We turn our attention to a night earlier in December 1940 when Lee, Hither Green and parts of the Corbett Estate were again hit – the night of 8-9 December 1940 – most of the bombs fell in a short period around 11:00 pm on the Sunday evening.

As was the case with the raids almost three weeks later, Lee wasn’t the real target and was a stopping off point on a major raid on London during which German bombers dropped over 380 tons of high explosive bombs and at least 115,000 incendiaries. 250 Londoners were killed on 8 December and 600 more seriously injured. Several streets in Lee, such as Brightfield Road (below), were hit in both raids.

As we have found with other posts on the Blitz, including the first night and the raids on 27 December and 29 December 1940, it is worth remembering that not every incident was reported to the Air Raid Precautions (ARP) HQ at Lewisham Town Hall, some being just reported to the Fire Brigade but others never going through official channels. This is particularly the case with incendiary bombs which residents were often able to put out themselves.

This particular night was clearly chaotic at the ARP HQ with some incidents clearly being reported and/or written up several times – as far as possible the narrative and maps have attempted to strip out the duplicates. There were around 70 incidents reported in just Lee, Hither Green and the Corbett Estate with no doubt lots not reported and large numbers elsewhere in the old Borough of Lewisham.

So, what were incendiary bombs? They were cylindrical bombs around 35cm long, and 5cm in diameter. Inside was a mechanism that ignited an incendiary compound that filled the cylinder, thermite, on impact. They were often dropped in ‘breadbaskets’ typically containing 72 incendiaries.

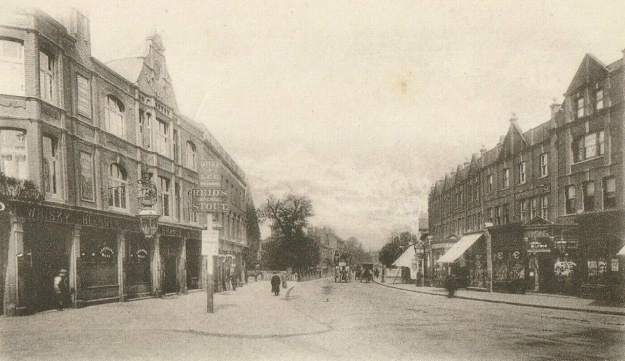

There appear to have been at least three ‘breadbaskets’ dropped on Lee at around 10:50 pm– one around Wantage Road, another on Burnt Ash Road, although the numbers were smaller there and a third around Brightfield Road. There were around 70 incendiaries that the ARP logged – with most, the note on the log was ‘fire put out without significant damage to property.’ The fires in Brightfield Road were of a different class to those elsewhere though– the ARP log noted that they were ‘distinguished’ – presumably a typo. Several of the houses in the postcard above were hit, whilst the photograph was taken over 30 years before, the street scene, that much will not have changed by 1940. The locations recorded from the raid in Lee are mapped below.

There were relatively few injuries – those that there were tended to be from the aftermath and/or trying to put out fires – four were injured in Burnt Ash Road, including a child who was blinded at 90 Burnt Ash Road and an ARP warden was injured in Micheldever Road.

At around the same time as incendiaries rained down on Lee several were dropped around what was then Campshill House in Hither Green Lane, Ryecroft and Campshill Roads (at the top of the map below). A few minutes later there were a couple in the streets to the north of Brownhill Road – Ardgowan and Springbank Roads (there is a separate post on attacks on Springbank Road.) There were also incendiaries dropped in Fernbrook Road – 67 and 101 were both damaged along with another two at 127 Manor Park and Leahurst Road area (see Lee map above). No doubt a few more fell but weren’t recorded.

At about 11:05 it seems that a ‘breadbasket’ was dropped on the eastern side of the Corbett estate with several hits on Verdant Lane and a lot falling in Minard Road (pictured below) – although they mainly landed in the street. Whilst this would have destroyed cars in 2021, this presumably wasn’t much of an issue in 1940.

While in the main, it was incendiary bombs that hit Hither Green, Lee and the Corbett Estate that night, there were a few high explosive bombs dropped too. The earliest was in Nightingale Grove at the junction with Maythorne Cottages (the eastern side of the ‘tunnel’ and current main entrance to Hither Green station.) It failed to explode, but the road was closed and, presumably, residents evacuated at around 10:00 pm. Three and a half years later, more or less the same location was hit by a V-1, causing several deaths and the destruction of a lot of homes.

Around 45 minutes later another one exploded at the junction of Mount Pleasant and Fordyce Roads causing a crater in the road and damaging the water supply. Another unexploded high explosive bomb was reported at 59 St Mildred’s Road around 1:00 am, it was probably dropped earlier in the evening and the residents were evacuated.

The most destructive high explosive bomb was reported at 11:30 pm – at the junction of Dacre Park and Eton Grove, close to Lee Terrace. Two houses were demolished and several others were damaged beyond repair. Dacre Park was blocked for a while and four were reported as being injured.

One of those injured was William John Sherriff, a 21-year-old merchant seaman from Port Talbot in South Wales; William was taken to Lewisham Hospital but died there the following day.

While of a similar size to the site from the Fernbrook Road V1 and several around Boone Street, the old Brough of Lewisham did not prefabs built on it; the site was cleared and flats built on it soon after the war, pictured below.

As noted earlier, Lewisham wasn’t the primary target of the raid – the bombers moved on towards central London where a high explosive bomb demolished the south and east sides of the Cloisters of St Stephen’s Chapel within the Houses of Parliament. The BBC buildings in Portland Place were badly damaged that night too.

Notes

- In several locations the term ’many’ was used in the ARP log – this includes the both the eastern and western sides of Burnt Ash Road, Effingham Road (around the current Brindishe School), the eastern end of Burnt Ash. In these cases, I have assumed at least four incendiaries fell. Some also aren’t exact – one group of four were noted as being on Micheldever between Wantage and Burnt Ash Roads.

- The numbers are undoubtedly an underestimate – incendiary bombs that harmlessly fell in gardens or roads probably wouldn’t have been reported.

Credits

- Most of the information for this post comes from the Lewisham ARP Log – it is a fascinating document, which is part of the collection of Lewisham Archives.

- The postcard of Effingham Road is via eBay in February 2018

- The maps are created via Google Maps